MARGARET THE FIRST

DANIELLE DUTTON

Catapult

$15.95 trade paper, available now

Rating: 6* of five

The Publisher Says: Margaret the First dramatizes the life of Margaret Cavendish, the shy, gifted, and wildly unconventional 17th-century Duchess. The eccentric Margaret wrote and published volumes of poems, philosophy, feminist plays, and utopian science fiction at a time when “being a writer” was not an option open to women. As one of the Queen’s attendants and the daughter of prominent Royalists, she was exiled to France when King Charles I was overthrown. As the English Civil War raged on, Margaret met and married William Cavendish, who encouraged her writing and her desire for a career. After the War, her work earned her both fame and infamy in England: at the dawn of daily newspapers, she was “Mad Madge,” an original tabloid celebrity. Yet Margaret was also the first woman to be invited to the Royal Society of London—a mainstay of the Scientific Revolution—and the last for another two hundred years.

Margaret the First is very much a contemporary novel set in the past, rather than “historical fiction.” Written with lucid precision and sharp cuts through narrative time, it is a gorgeous and wholly new narrative approach to imagining the life of a historical woman.

My Review: Every year, there is one book...rarely are there two...that moves me so profoundly and give me so much reading joy that I need to give it the highest, best accolade I possess: This book broke the scale. This is the bar I'll be judging many other books by. We're pretty much done with the first half of 2016 and I was getting a bit restless for a sighting of the six-star book. I've read some excellent books this year, but until Danielle Dutton's publisher, Catapult, sent me this book at my request, none that would come close to the six stars level.

He tapped his hat for shade. A crow pecked near his feet. He was about to give it up, and then: 'Mad Madge!' someone cried in the street. 'Mad Madge!' someone repeated, as her black-and-silver carriage came roaring down the path. But the horses were forced to a stop, for the crowd had grown to a mob. 'I see her,' someone shouted. He saw her then, through the window glass--black stars, white cheeks. That night in his diary he wrote: 'The whole story of this lady is a romance, and everything she does.'Pepys, on page four. Okay then, thinks I, we're on the way up from five stars on page four! The golden apple is Ms. Dutton's to lose.

She never lost it. Never came close.

The early days of Margaret Lucas's life were fairly typical of those for a girl of her station. She was from minor nobility, the county set as it would come to be called. She was odd even to her family, she was not meant to fit in anywhere, and she honestly seems never to have tried. It was her bad luck to be born at the time of the Civil War, and to a Royalist family. Her entire life she would deal with, be circumscribed by, defined by the Civil War and its long, long aftermath. Her youth was spent in various exiles, for example Paris, where the English Queen Henrietta Maria had Margaret as a very junior and unpopular lady-in-waiting:

"'I had rather be a meteor, single, alone.'How did a teenaged girl, in an era that discouraged all non-conformity and frequently punished female "rebelliousness," reach the strength of mind to think such thoughts and the strength of character to live her life according to that simple principle, so hard to do? It has to be something inborn. Anyone who has ever parented an infant knows that they arrive with personalities (blank slates my lily-white patootie!). What must Margaret's beloved mother have gone through, worrying about her willful young daughter so far away from her almost all their lives?

Plus Paris itself was noisome. Even with its glittering bridges and orangeries, even if the birthplace of ballet.

'I had rather been a meteor, than a star in a crowd.'"

Mother needn't have worried too much. While at Queen Henrietta Maria's court, Margaret meets the widowed, exiled Marquess of Newcastle, a man more than twice her age with adult children. Ordinarily this would be unremarkable; Margaret isn't considered marriageable. The Marquess, however, disagrees; he falls in love with her very oddness and originality of mind. This is one amazingly lucky woman. The Queen, whose consent to such an alliance is necessary, doesn't stand in the way but expresses her amazement that such a bizarre match could take place.

Life as an aristocratic exile is precarious. Money is tight, sources of income lost, and only the Queen repaying a loan let the newlyweds enjoy a modestly comfortable exile in Antwerp (much cheaper than Paris!). All of Holland was then and is now quite cosmopolitan, so the new Marchioness is exposed to many, many new ideas, people she would never meet in Paris or London (Jews!), and she revels in it all with her loving and supportive husband:

One night, the Duarte girl sang poems set to music in a voice so clear I felt my soul rise up inside my ear. In a garden of clematis, with servants dressed like Gypsies placing candles in the trees, we assembled on the grass, between a Belgian wood and {the Duchess of Lorraine}'s glassy pond. In a pale orange gown I read two pieces I'd prepared...When the ladies clapped their approval in the dark, everything, to me, was suddenly bright and near.How amazing for the shy Marchioness to read in public, how delicious to be applauded, how very different from any life she could reasonably have expected to have. And how perfect Dutton's prose is, representing such a magical moment. I was starry-eyed myownself when I read that passage.

Margaret's response to such an extraordinary life is to become even more extraordinary herself. She writes a book published under her own name, with her husband William's complete and excited support; encouraged by that and the kerfuffle she has caused in the educated world, she publishes a second and then third book. Writing has become a way of life, an addiction, a refuge and a podium both:

Still, Antwerp, the parties, my husband's talks--all of it fed my mind. I'd hardly set down my quill before I took it up again, writing stories unconnected--of a pimp, a virgin, a rogue--strung up like pearls on a thread. ... 'I am very ambitious, yet 'tis neither for Beauty, Wit, Titles, Wealth, or Power, but as they are steps to raise me to Fames Tower.'Anyone whose writing has caused others to respond strongly will know how the Marchioness feels.

O minor victory! O small delight! My star began to rise.

And of course, this being the world ruled by evil-tempered gods, all good things come to an end. William and Margaret, in need of money to live and desiring the return of estates confiscated by the ended Republic, cash in on the Marchioness's fame and the restored King's interest in her outrageous persona. A fête in His Majesty's honor is held:

'An utter success,' her stepdaughters confided to Margaret as they prepared to take their leave. 'The handsome king! That spoof!' Still the rain persisted, and the bishop had lost his hat. Maids danced in and out. Where was the bishop's hat? Alone at the window, Margaret didn't hear. The reflection of the parlor was yellow and warm. She watched it empty out. Then, an interruption. A voice came at her side: 'What do you look at with such interest, Lady Cavendish?' What did she see in the glass? She saw the Marchioness of Newcastle. She saw the aging wife of an aged marquess, without even any children to dignify her life.The Marchioness's interlocutor is one Richard Flecknoe, a young man barely known to her in Holland, and who becomes her playmate and teacher and arm-candy. William, bless him, voices faith in and approval of Margaret's friendship, canceling any scandal.

And then (you know what's coming, right?) William and Margaret leave their precarious London existence for the newly returned Cavendish estates near Colchester. As soon as things begin to go smoothly.... But the most wonderful thing happens while they are there: Margaret's long-missing crates of writings, her "modest closet plays," arrive and are printed at last:

She was reading Francis Godwin's Man in the Moone--its man was borne into space in a carriage drawn by swans--when she heard the sound of wheels upon the gravel. Two boxes from Martin & Allestyre were set down on the drive. 'My modest closet plays,' she said. She nearly ran down the stairs--for the recovery of her wayward crates that spring and the preparation of her plays for publication had rekindled inside Margaret a flame she'd feared had gone out. ... But now, in turning the pages, she grew concerned and then incensed: 'reins' where she had written 'veins,' 'exterior' when she had clearly meant 'interior.' The sun went down. The room grew dim. ... 'Before the printer ruined it,' she cried, 'my book was good!'An autodidact, Margaret's spelling is, ummm, idiosyncratic; a passionate writing addict, she's always rushing through her work to begin something new. In spite of her resentment of William's criticism, she goes to work to fix the book's problems as he advises.

'Could it be,' {her husband} asked, soaking his bread in {lamb's} blood, 'that you were yourself the cause of this misfortune?'

As life goes on, as she grows older in body, she grows more and more powerful in her mind and fearless in her imagination:

On the fifth night of this solitude, she falls asleep with a candle burning and dreams herself a mermaid with a thick and golden tail, a crown of shimmering conch shells, then awakens with a start. Whether the ship hit something or something hit the ship, another change has come. The ship is dying; she can feel it slipping away. She waits beneath the blanket for icy water to greet her. But instead of the sea, it's a bear that opens the door.The writing of a seventeenth-century woman, elderly by the standards of the day. This is simply glorious imagination, simply astonishing to realize it is over 350 years old. This childless woman, forgotten by our modern world and only "famous if you know who she is," would be delighted to be brought to vivid life again by Danielle Dutton. How can I be sure of that?

A great white bear up on its hind legs steps across the threshold.

'Good morning,' he says, and reaches out a paw.

Off come her skirts and petticoats, her lace cuffs and collar, her shoes and whalebone stay, until she lies on her side in nothing but a cotton shift and endless strands of pearls. Dust hangs in a crack of light between red velvet drapes, like stars.Show me a writer, past or present, who would not beam joyfully at being so unclothed, so beautifully described, so wonderfully and comprehensively understood.

Her dreams are glimpses, bewildered--celestial charts, oceanic swells, massive, moving bodies of water, the heavens as heavenly liquid, familiar whirlpools, the universe as a ship lost at sea--but the ship she imagines arrived safely, years ago, loaded with their possessions.

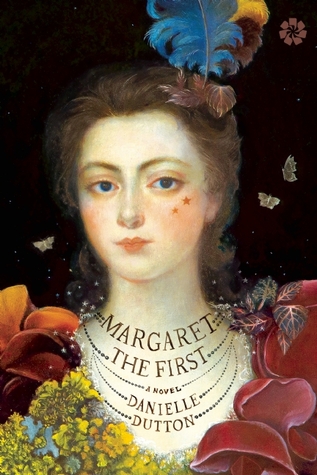

It is Dutton's gift to write beautifully. It is also her gift to find the perfect publisher for her work. The cover is glorious; the design of the book is lovely, and completely transparent to anyone not looking for it; it is, in short, an author's dream of a book. Equally it is a publisher's dream to publish a novel about a now-obscure woman dead for centuries about which a jaded old reviewer (ie, me) can, completely without reservation or reluctance, say that this book is:

Yet how hard it is to point to a moment. To say: there, in that moment, I changed.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.