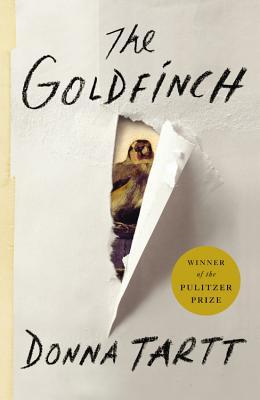

THE GOLDFINCH

DONNA TARTT

Little, Brown

$30.00 hardcover, available now

Rating: 4* of five

The Publisher Says: It begins with a boy. Theo Decker, a thirteen-year-old New Yorker, miraculously survives an accident that kills his mother. Abandoned by his father, Theo is taken in by the family of a wealthy friend. Bewildered by his strange new home on Park Avenue, disturbed by schoolmates who don't know how to talk to him, and tormented above all by his unbearable longing for his mother, he clings to one thing that reminds him of her: a small, mysteriously captivating painting that ultimately draws Theo into the underworld of art.

As an adult, Theo moves silkily between the drawing rooms of the rich and the dusty labyrinth of an antiques store where he works. He is alienated and in love-and at the center of a narrowing, ever more dangerous circle.

The Goldfinch is a novel of shocking narrative energy and power. It combines unforgettably vivid characters, mesmerizing language, and breathtaking suspense, while plumbing with a philosopher's calm the deepest mysteries of love, identity, and art. It is a beautiful, stay-up-all-night and tell-all-your-friends triumph, an old-fashioned story of loss and obsession, survival and self-invention, and the ruthless machinations of fate.

My Review: The Doubleday UK meme, a book a day for July 2014, is the goad I'm using to get through my snit-based unwritten reviews. Today's prompt is to identify the book one would take to a desert island.

It was between this book and The Luminaries, a more artistically successful and more culturally enriching book; a book with grace and beauty and charm; a rich feast that says things to me even yet, months after reading it.

I chose this book.

I look at the blanked-out faces of the other passengers--hoisting their briefcases, their backpacks, shuffling to disembark--and I think of what Hobie said: beauty alters the grain of reality. And I keep thinking too of the more conventional wisdom: namely, that the pursuit of pure beauty is a trap, a fast track to bitterness and sorrow, that beauty has to be wedded to something more meaningful.It's not Art, but it's a good, solid, real moment. I bought into Theo, I cared about the dumbass, I found him the kind of kid I'd try to fix and straighten out so he wouldn't flounder so messily as he looked for the path through the thicket.

Only what is that thing? Why am I made the way I am? Why do I care about all the wrong things, and nothing at all for the right ones? Or, to tip it another way: how can I see so clearly that everything I love or care about is illusion, and yet--for me, anyway--all that's worth living for lies in that charm?

A great sorrow, and one that I am only beginning to understand: we don't get to choose our own hearts. We can't make ourselves want what's good for us or what's good for other people. We don't get to choose the people we are.

Then there's traife like this: "'When you feel homesick,' he said, ‘just look up. Because the moon is the same wherever you go.'” Gag me. That's so Disney-movie pseudoprofound I could unswallow all over the book.

But then...

Whatever teaches us to talk to ourselves is important: whatever teaches us to sing ourselves out of despair. But the painting has also taught me that we can speak to each other across time. And I feel I have something very serious and urgent to say to you, my non-existent reader, and I feel I should say it as urgently as if I were standing in the room with you. That life—whatever else it is—is short. That fate is cruel but maybe not random. That Nature (meaning Death) always wins but that doesn’t mean we have to bow and grovel to it. That maybe even if we’re not always so glad to be here, it’s our task to immerse ourselves anyway: wade straight through it, right through the cesspool, while keeping eyes and hearts open. And in the midst of our dying, as we rise from the organic and sink back ignominiously into the organic, it is a glory and a privilege to love what Death doesn’t touch.Sadly, it goes on after that to bury the well-made point and the well-turned phrase in verbiage.

Donna Tartt won a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in recognition of this novel. I am not equipped with the information the judges of that prize use to make their decision. I can only say that, from my perspective as a reader, this is a good, solid read that should've been 600pp not 771pp, with many lovely phrases and a lot of good, well-incorporated action, but not especially prize-worthy. It's a thumping good read, as my friend Suz says.

And for that reason, I'd take it to a desert island, and I'd cuss and fume and fret about its shortcomings after I finished each read wet-eyed about Theo and his travails. Sometimes Theo acts so damned clueless I wanted to give him a bloody box of chocolates and a bench and plant a Barnaby Rudgely raven called Grip on his damn shoulder. And then:

You could study the connections for years and never work it out--it was all about things coming together, things falling apart, time warp, my mother standing out in front of the museum when time flickered and the light went funny, uncertainties hovering on the edge of a vast brightness, the stray chance that might, or might not, change everything.So, yeah, this is the one that makes the desert island trip. Sorry, Eleanor Catton, your gorgeous and so very deserving tome will wait for me safe on my shelf.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.